The BSR/BHPR Guideline for Scleroderma - what does it mean for patients?

Over the past 2 years an intensive amount of work has been undertaken to develop the first national UK guideline for treatment of scleroderma. This has been a group effort performed on behalf of the BSR (British Society of Rheumatology) and BHPR (British Health Professionals in Rheumatology) to develop an expert driven evidence based series of recommendations for the management of scleroderma.

Over the past 2 years an intensive amount of work has been undertaken to develop the first national UK guideline for treatment of scleroderma. This has been a group effort performed on behalf of the BSR (British Society of Rheumatology) and BHPR (British Health Professionals in Rheumatology) to develop an expert driven evidence based series of recommendations for the management of scleroderma. It focuses on systemic sclerosis and has been a concerted effort from a dedicated group of experts, patients and healthcare professionals. The work is now completed and the full guideline has been published on the BSR website [1] and an executive summary published in the international journal Rheumatology. Both of these documents are freely available.

These guidelines are important because they summarised the current best practice for treating the major complications of systemic sclerosis and also address the overall approach to disease management in the UK. They have been developed under the auspices of the SAGWG (Standards, Audit and Guidelines Working Group) of BSR that has developed a process that is accredited by NHS evidence. This is important since it means that the guideline is NICE accredited and should therefore be taken very seriously within the NHS as defining the standard of care for patients and access to therapies. Embedded within the guideline are important NHS England policies for the management of digital ulcers and the pathway developed for assessment and delivery of autologous stem cell transplantation for appropriate cases of diffuse systemic sclerosis.

The guideline process involved establishing a development group that included rheumatologist, scleroderma experts, pharmacists, allied healthcare professionals, specialist nurses, primary care representatives and patients. In this way all aspects of the disease and management could be included. A comprehensive literature review of all the evidence supporting treatments for scleroderma was an important starting point and a group of dedicated clinical fellows undertook this work. There was a series of telephone and face to face meetings over 2 years that led to the development of the draft guideline This was then reviewed by BSR SAGWG and by external; referees. Comments were incorporated and the revised guideline was then finalised and submitted for open consultation so that anyone could comment and have input. After this process the final guideline was written, this was submitted for approval of BSR and then for publication in Rheumatology [2].

This is not the end of the process since the guideline are reviewed and updated every 5 years according to NHS Evidence protocols. This is a landmark for UK scleroderma patients and an important one at a time of major NHS change and also challenged and competition for resources for rare diseases. It complements the other recommendations being updated such as this of EULAR (European League Against Rheumatism) and the UKSSG (UK Scleroderma Study Group) best practice consensus documents [3].

Professor Chris Denton, Royal Free Hospital and UCL Division of Medicine

Chair of the BSR/BHPR Scleroderma Guideline development working group

References for more information:

- BSR Guideline executive summary – Rheumatology 2016 (in press)

- UKSSG Consensus Best Practice Documents

BSR and BHPR guideline for the treatment of systemic sclerosis

- Christopher P. Denton1, Michael Hughes2, Nataliya Gak1, Josephine Vila3, Maya H. Buch4, Kuntal Chakravarty1, Kim Fligelstone1, Luke L. Gompels5, Bridget Griffiths3, Ariane L. Herrick2, Jay Pang6, Louise Parker7, Anthony Redmond4, Jacob van Laar8, Louise Warburton9, Voon H. Ong1, on behalf of the BSR and BHPR Standards, Guidelines and Audit Working Group

Author Affiliations

- 1Centre for Rheumatology, Royal Free Hospital, London

- 2Rheumatology Department, Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust, The University of Manchester, Manchester Academic Health Science Centre, Manchester

- 3Department of Rheumatology, Freeman Hospital, Newcastle upon Tyne

- 4Leeds Institute of Musculoskeletal and Rheumatic Medicine, Chapel Allerton Hospital, Leeds

- 5Rheumatology Department, Musgrove Park Hospital, Taunton,

- 6Pharmacy Department

- 7Centre for Rheumatology, Royal Free Hospital, London, UK

- 8Rheumatology and Immunology, UMC Utrecht, Utrecht, The Netherlands

- 9Primary Care, Telford and Wrekin NHS Trust, Telford, Shropshire, UK

- Correspondence to: Christopher P. Denton, Centre for Rheumatology and Connective Tissue Diseases, Royal Free Hospital and UCL Medical School, Pond Street, London NW3 2QG, UK.

Executive Summary

Scope and purpose

SSc is a complex, multi-organ disease that requires a comprehensive multidisciplinary guideline. This is a short summary of the guideline.

Eligibility and exclusion criteria

Patients are classified as having SSc based on current classification criteria (ACR/EULAR 2013 [1]). Other scleroderma spectrum diseases are not included in this document.

Part A: general approach to SSc management

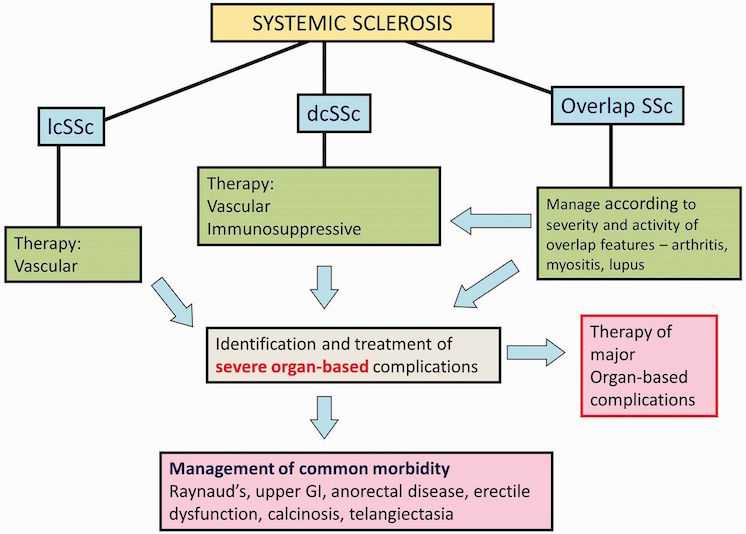

Figure 1 summarises a general approach to management of SSc.

Overview of management of SSc

The principles of current management of SSc are summarised. Once a confirmed diagnosis is established, all patients can be designated as either lcSSc or dcSSc subset based upon the extent of skin thickening. Proximal skin involvement, involving skin of trunk or proximal limbs, is designated diffuse. Cases with overlap disease should be identified so that overlap features may be treated concurrently with SSc. All patients require symptomatic treatment, and both limited and diffuse cases should be treated for vascular manifestations. Active, early dcSSc requires immunosuppressive treatment. In all cases of SSc, vigilant follow-up to determine significant organ-based complications is mandatory. dcSSc: diffuse cutaneous SSc; lcSSc: limited cutaneous SSc; GI: gastrointestinal.

Importance of early diffuse SSc: current priorities and approach

Management of early diffuse cutaneous SSc (dcSSc) should occur within the framework of a multidisciplinary team.

Recommendations in management of early SSc

- Early recognition and diagnosis of dcSSc is a priority, with referral to a specialist SSc centre (III, C).

- Patients with early dcSSc should be offered an immunosuppressive agent: MTX, MMF or i.v. CYC (III/C), although the evidence base is weak. Some patients might later be candidates for autologous haemopoietic stem cell transplant (ASCT; see below).

- D-Pen is not recommended (IIa/C).

- ASCT may be considered in some cases, particularly where there is risk of severe organ involvement, balancing concerns about treatment toxicity (IIa/C).

- Skin involvement may be treated with either MTX (II, B) or MMF (III, C). Other options include CYC (III, C), oral steroid therapy (in as low a dose as possible to suppress symptoms, and with close monitoring of renal function; III, C) and possibly rituximab (III, C).

- AZA or MMF should be considered after CYC to maintain improvement in skin sclerosis and/or lung function (III, C).

Part B: key therapies and treatment of organ-based disease

RP and digital ulcers

RP is almost universal and can be treated by vasodilators, but benefit must be balanced against side-effects. Around half of patients with SSc report a history of digital ulceration that reflects more structural vasculopathy. Severe digital ulcers (DUs) are those causing or threatening tissue destruction or when three or more occur in 1 year. These should be considered for advanced therapy, such as sildenafil, iloprost or bosentan [2].

Recommendations for RP in SSc

- First-line treatments are calcium channel blockers (Ia, A) and angiotensin II receptor antagonists (Ib, C).

- Other treatments that may be considered are: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, α-blockers and statin therapy (III, C).

- Phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors are being used increasingly for SSc-related RP (IIa, C).

- Intravenous prostanoid (e.g. iloprost; Ia, B) and digital (palmar) sympathectomy (with or without botulinum toxin injection) should be considered in severe and/or refractory cases (III, D).

Recommendations for DUs in SSc

- DUs require integrated management by a multidisciplinary team; management includes local and systemic treatment (III, C).

- Oral vasodilator treatment should be optimized, analgesia optimized and any infection promptly treated (III, C).

- Sildenafil should now be used before considering i.v. prostanoids and bosentan, in line with the current National Health Service (NHS) England Clinical Commissioning policy [3] (I, A).

- In severe active digital ulceration, patients should receive i.v. prostanoid (Ia, B). In patients with recurrent, refractory DUs, a phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor (IIa, B) or i.v. prostanoid (Ia, B) and an endothelin receptor antagonist (including bosentan; Ia, B) should be considered.

- Digital (palmar) sympathectomy (with or without botulinum toxin injection) may also be considered in severe and/or refractory cases (III, D).

Lung fibrosis

Up to 80% of SSc patients will develop interstitial lung disease, but this may be mild and stable. Immunosuppression should be considered when extensive or progressive disease is confirmed.

Recommendations for lung fibrosis in SSc

- All SSc cases should be evaluated for lung fibrosis. Treatment is determined by the extent and severity and the likelihood of progression to severe disease (I, A).

- CYC by i.v. infusion is recommended (I, A/B), and MMF may also be used as an alternative or after CYC (II, B).

Pulmonary arterial hypertension

For patients living in England, treatments are initiated through a designated Pulmonary Hypertension Centre (see NHS England A11/S/a) according to the national commissioning policy for treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH; NHS England/A11/P/b and NHS Commissioning Board (NHSCB)/A11/P/a), reflecting expert recommendations [4].

Recommendations for PAH in SSc

- Diagnosis should be based upon results of full evaluation of PAH, including right heart catheterization and evaluation of concomitant SSc-related cardiac or lung disease (I, A).

- Therapies licensed for PAH should be used in the UK Pulmonary Hypertension Centres, taking account of the agreed commissioning policies (I, A/B).

Gut disease

Gastro-oesophageal reflux is near universal and needs treatment. Other gastrointestinal (GI) manifestations include constipation, bloating, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, altered bowel habit and anorectal incontinence (overall management covered elsewhere [5]).

Recommendations for GI manifestations in SSc

The following therapeutic approaches and drugs are considered by experts to be of value in treatment of GI tract complications of SSc.

- Proton pump inhibitors and histamine H2 receptor antagonists are recommended for treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux and dysphagia and may require long-term administration (III, C).

- Prokinetic dopamine agonists may be used for dysphagia and reflux (III, C).

- Parenteral nutrition should be considered for patients with severe weight loss refractory to enteral supplementation (III, C).

- Intermittent broad-spectrum oral antibiotics (e.g. ciprofloxacin) are recommended for intestinal overgrowth, and rotational regimes may be helpful (III, C).

- Anti-diarrhoeal agents (e.g. loperamide) or laxatives may be used for symptomatic management of diarrhoea or constipation that often alternate as clinical problems (III, C).

Renal complications

SSc renal crisis (SRC) causes severe hypertension and acute kidney injury and without treatment is often lethal. It affects 5–10% of SSc patients, predominantly the diffuse subset.

Recommendations for treatment of SRC

- Patients at risk of SRC should be followed closely and their blood pressure monitored at least weekly (III, C).

- Prompt recognition of SRC and initiation of therapy with an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor offers the best opportunity for a good outcome (III, C).

- Other anti-hypertensive agents may be considered for management of refractory hypertension in conjunction with an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor in SRC (III, C).

Cardiac disease

Clinically evident cardiac involvement includes diastolic or systolic heart failure, arrhythmia and conduction disturbances and has a significant mortality.

Recommendations for treatment of cardiac manifestations of SSc

Although the published evidence base is limited, experts have recommended the following treatment approach for cardiac complications of SSc.

Systolic heart failure

- Consider immunosuppression with or without a pacemaker (IV, D).

- Consider the potential benefit of an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (III, D).

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and carvedilol. Selective β-blockers may be considered, but consider aggravation of RP (IV, D).

Diastolic heart failure with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction

- Diuretics, including spironolactone and furosemide (IV, D).

- Calcium channel blockers have been shown to reduce the frequency of systolic heart failure in SSc with investigational evidence of cardiac abnormalities (III, D).

Skin manifestations

Treatment of skin thickening, assessed by modified Rodnan skin score, is central to management of dcSSc treatment, and pruritus is common and troublesome in early stage disease.

Recommendations for skin manifestations in SSc

- Practical approaches to ensure adequately moisturized skin are essential, especially moisturizers that are lanolin based (III, C).

- Antihistamines are often used for itch (III, C).

- Current treatment options for telangiectasia include skin camouflage and laser or intense pulsed light therapy (III, C).

Calcinosis in SSc

There is a very limited evidence base (mainly case reports and small series) to guide clinicians on the management of calcinosis in patients with SSc.

Recommendations for treatment of calcinosis in SSc

- Calcinosis complicated by infection should be recognized early and treated with appropriate antibiotic therapy (III, D).

- Surgical intervention should be considered for severe, refractory calcinosis, which is severely impacting upon functional ability and quality of life (III, D).

Musculoskeletal manifestations

Musculoskeletal involvement includes tendinopathy, joint contractures and, in some cases, overlap arthritis.

Recommendations for musculoskeletal manifestations in SSc

- Musculoskeletal manifestations of SSc may benefit from immunomodulatory treatments given for other complications, such as skin disease (III, C).

- When arthritis or myositis is more severe, generally in the context of an overlap SSc syndrome, management is in line with similar clinical conditions occurring outside the context of SSc (III, C).

ASCT as a treatment for poor prognosis early dcSSc

Haematopoietic stem cell transplant registry data, several case reports and pilot studies in the USA and Europe in dcSSc demonstrated a rapid clinical improvement, but with important treatment-related mortality [6].

Recommendation for ASCT in SSc

- Current evidence supports use of ASCT in poor-prognosis diffuse SSc where patients do not have severe internal organ manifestations that render this treatment option highly toxic (Ib, B).

Non-drug interventions

Although the evidence base is limited, non-drug interventions may have merit and are well tolerated.

Recommendation for non-drug interventions in SSc

- Specialist experience of SSc cases is likely to make non-drug interventions more effective, and these approaches are popular with patients and can be expected to impact positively on the disease. More research is needed in this area (III, D).

Part C: service organization and delivery within NHS England

SSc should be diagnosed promptly, investigated appropriately and managed within an integrated system of primary, secondary and tertiary level care.

Funding: No specific funding was received from any bodies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors to carry out the work described in this manuscript.

Disclosure statement: C.P.D. has been a consultant to Actelion, GlaxoSmithKline, Bayer, Inventiva, Takeda and Roche and received research grants from CSL Behring, Novartis and Actelion. J.v.L. has been a consultant for MSD, Pfizer, Roche, BMS and Eli Lilly. A.L.H. has been a consultant to Actelion and Apricus, has spoken at meetings sponsored by Actelion and received research funding from Actelion. All other authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Featured on http://rheumatology.oxfordjournals.org